How Giant Amazon Warehouses Are Choking a California Town

Ontario was once at the center of the dairy industry. Now it's home to Amazon's largest warehouse and hundreds of others—with dangerous consequences.

Edgar Jaime didn’t realize that the largest Amazon warehouse in the world was being constructed across the street from his vegetable farm in Ontario, Calif., until the walls went up.

Then again, Jaime can’t say he was too surprised.

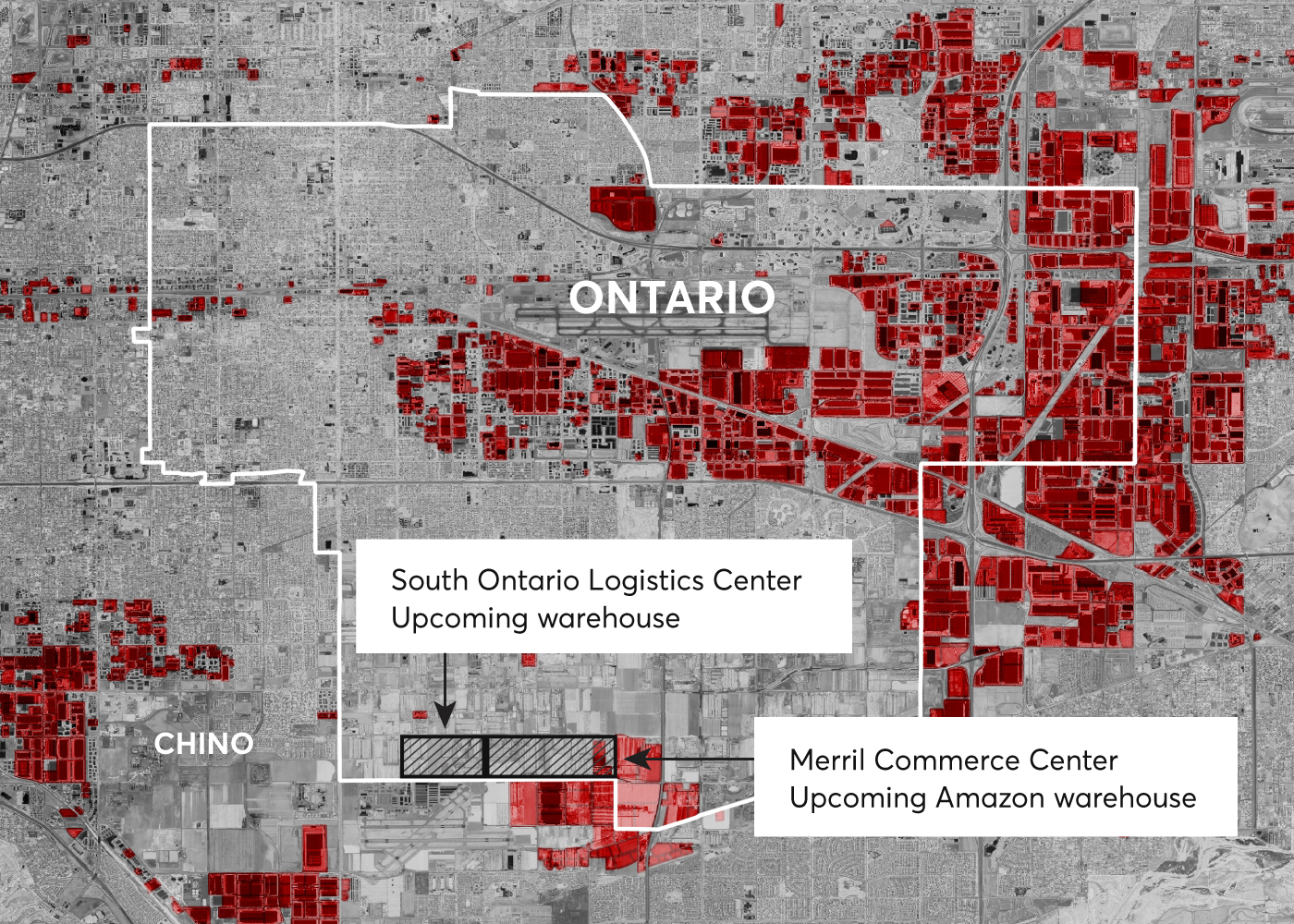

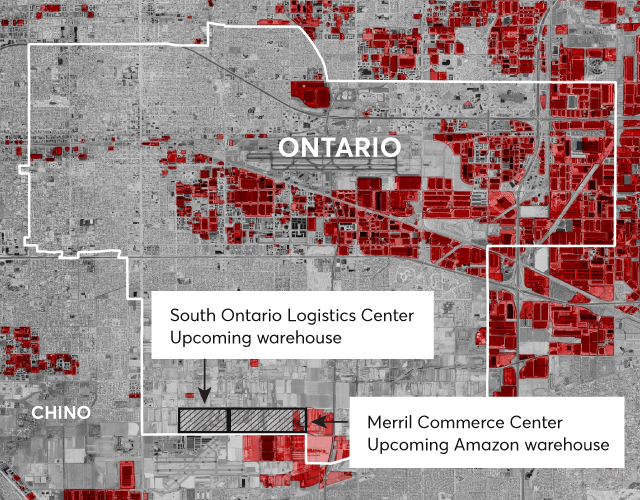

Over the past decade, once bucolic Ontario has become one of the biggest U.S. hubs for the e-commerce industry. In addition to the 4.1 million-square-foot Amazon facility under construction, three other Amazon facilities, as well as a sprawl of warehouses for FedEx, Nike, and other companies, stretch to the east of Jaime’s farm. A 5.1 million-square-foot logistics center will soon be constructed down the road.

Tombstones on Family Legacies

For Galván, a 32-year-old who grew up in Ontario and now works in residential and retail real estate, the new, sleek greige warehouse can look like tombstones atop long-running family legacies. “I believe in development, I support construction,” Galván says. “I’m not against tearing stuff down to build something better.” But she misses the wide-open public land, the sprawling citrus groves, and the family farms she grew up with.

Ontario had long been a dairy town, settled by Dutch, Portuguese, and Basque farmers in the late 1800s and early 1900s. By the 1980s, the area was one of the highest-yield milk-producing regions in the world. At the same time, starting midcentury, families began moving to the region from Los Angeles and the Midwest, including many Black and Latino families like the Galváns. Here, they found affordable homes with access to open spaces.

“The money folks worked hard to make in L.A. went a lot farther there,” says Juan Galván, Andrea’s father.

But urbanization and the expansion of industry in the region soon pushed the dairies out. In the 1980s, ’90s, and the early aughts, farmers began selling their land and moving to the Central Valley—closer to milk and cheese processing plants, and to other farms willing to buy manure for fertilizer.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian

Then the logistics industry took off.

Companies were drawn in by Ontario’s proximity to the L.A. and Long Beach ports—the two busiest in the country—and its network of major freeways. Especially amid the Great Recession, local leaders welcomed the industry and its promise of jobs.

Today, more than 600 warehouses are clumped into Ontario’s 50 square miles. A mapping tool developed by researchers at the Robert Redford Conservancy at Pitzer College in Claremont, Calif., and the consulting firm Radical Research estimates that altogether, warehouses take up 16 percent of the city’s land.

Nearly 100 of the warehouses opened in just the past three years, to feed the country’s ever-growing hunger for online shopping.

Many Ontario residents say what really shook them up was the realization that their city could soon be home to the largest Amazon warehouse in the world.

The five-story, 4,055,000-square-foot behemoth spans about a fifth of the size of Disneyland in California. According to the consulting firm MWPVL International, which tracks Amazon’s distribution network, the site is Amazon’s biggest known warehouse. Once it’s up and running in 2024, 1,500 employees will work alongside robotic systems, to send out an estimated 125 million packages a year.

The construction had been in the works for years, though its ultimate scope and purpose would long remain unclear. The project was proposed in 2019 by Prologis, a real estate firm that frequently works with Amazon. Amazon’s name, however, wasn’t officially associated with the project. The initial plans suggested a “business park” featuring smaller buildings as well as “larger warehouse-style buildings,” according to planning documents presented by Prologis.

An environmental analysis submitted with the proposal said that emissions of greenhouse gasses, particle pollution, and nitrogen oxides would increase as the result of the project, and this impact will be “significant and unavoidable.”

Still, Ontario’s city council unanimously approved the project in April 2021.

By early 2022, plans had propped up for an even bigger construction—the 5.3 million-square-foot South Ontario Logistics Center, which developers wanted to build right next to the Amazon center.

Conservationists say delivery trucks going into and out of the center would emit even more greenhouse gasses—and run counter to the city’s goals to address the climate crisis. Environmental justice leaders say these trucks would further pollute the air.

But once again, the council passed the project 7-0.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian

"It Was Bound to Happen"

For many longtime residents, the massive new constructions are bookends to an era. “The land I grew up on is now covered in concrete,” says Craig Imbach, 58.

Imbach’s family sold off its dairy business in 1979. Two years ago, his old house was knocked down as well to make way for an industrial complex. All that remains are the sepia-toned photographs framed in his new home, and an heirloom collection of antique milk pails.

“I guess it was bound to happen,” Imbach says. He now works in construction—for a while he was building warehouses, though he has since transitioned to working with heavy machinery and often contracts with natural gas businesses.

“It’s bittersweet,” adds his wife, Jerrina Imbach, 54. The warehousing industry generates much-needed employment and infrastructure, she says. “But we lose the family farm, we lose the dairies,” Craig says.

Decades after his family farm was sold, Craig can’t bring himself to drink milk from a grocery store. “What can you do,” he says. “There’s no stopping progress.”

Then again, the town has been deeply divided over what that progress should look like.

At Flo’s Café—a classic old dinner housed in a nondescript little hut across from the new developments—the walls are still decorated with odes to the region’s history. There are paintings of happy Holstein cows and a poster of vibrant Holland tulips—an homage to the Dutch dairymen who settled the area in the 1900s.

At lunchtime on a recent Wednesday, the men of an old dairy family—one that sold its plot of land to warehouse developers for more than $1 million per acre—settled in next to a table of contractors working on one of the new logistics center constructions.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian

A few tables over, Randy Bekendam, a fourth-generation farmer, settled in with a group of local activists fighting new warehouse developments. Snide glances and polite smiles were exchanged before everyone tucked into their hot country sandwiches and tuna melts.

“This has been a longtime meeting place for farmers,” says Bekendam, a sun-hardened and spry 70-year-old in a cattleman’s straw hat and plaid shirt whom most people around here call “Farmer Randy.” “Nowadays I guess it can get a bit tense in here.”

Bekendam and his daughter run Amy’s Farm, a 10-acre regenerative farm with a half-dozen beef cattle, dairy cows called Buttercup and Tatertot, pigs, horses, 100 or so chickens, and a small herd of pygmy goats. Volunteers from the community come by to help harvest seasonal fruits and vegetables, school groups visit to learn about agriculture, and toddlers come to pet the goats.

Amid the warehouse boom, Bekendam’s landlord started receiving offers to sell the land to developers, Bekendam says. The farmer has filed a lawsuit in a bid to keep his farm and has joined up with a group of local leaders fighting the incursion of warehousing in Ontario.

“They keep building these monstrosities in the middle of farmland,” he says. “And once farmers are displaced that’s usually the end of their line.”

He and other activists want to see at least some of Ontario’s open land preserved for regenerative farming and community gardens—pockets of clean air and natural beauty.

“That’s something we really need,” he says.

Dangerous Air

Ontario has long struggled with horrendous air quality. Though longtime residents are now nostalgic for the astringent smell of manure, the bigger industrial dairies stunk up some neighborhoods. They also emitted methane, a powerful greenhouse gas that can interact with other pollutants to create suffocating levels of ground-level ozone. Smog from freight railways, factories, and farms collected over the Inland valley, in a cup created by the surrounding mountains. Generations of families suffered from asthma and recurring bronchitis.

Environmental regulations helped clear out the heavy, gray smog that Bekendam and other longtime residents recalled from the 1960s and ’70s. But warehouses have once again deteriorated air quality, activists say.

Researchers from the Redford Conservancy and Radical Research estimate that the perpetual procession of trucks in Ontario make about 96,000 trips into and out of the warehouses each day, producing about 8 million pounds of carbon dioxide emissions, 15,200 pounds of nitrogen oxide pollution, and 131 pounds of diesel particulate matter daily.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian

About 10 percent of children under 10 in San Bernardino County have been diagnosed with asthma, according to public heallth data compiled by the University of California, Los Angeles. About 36 percent of kids in this group were taking daily medication for asthma symptoms. A 2021 report from the local air quality monitoring management office found that people living within half a mile of warehouses had higher rates of asthma and heart attacks than residents in the region overall.

A joint investigation by Consumer Reports and the Guardian last year found that the rapid expansion of warehousing in the Inland Empire and other communities across the U.S. disproportionately affected poorer people and people of color.

Melissa May, a local organizer who began rallying residents to fight the South Ontario Logistics Center this year, says she stopped buying from Amazon and other online retailers once she understood the industry’s impact. “Now I tell all my friends in other parts of the country—don’t do it,” she says. “Your online shopping is directly hurting my community.”

May, who grew up in Ontario and lives a mile east of the new mega-constructions, moved back to the city in 2019 to take care of her sick father. She moved from Alexandria, Va., not far from where Amazon is building its second corporate headquarters, to where the company will open its biggest warehouse. And she says she and her whole family have seen their health deteriorate. “I just didn’t realize what we were moving back to,” she says.

May has asthma, chronic inflammatory lung disease, and emphysema, and says her conditions have become harder to manage since she moved back. Her 12-year-old son has asthma, too, she says, adding that like many kids in the area he gets frequent, gushing nosebleeds after playing outside. He had stopped getting those when they lived in Virginia, she says.

As she talks she pops one breath mint after another, one of several precautions she takes to avoid asthma attacks, sinusitis, and trips to the emergency room. She does breathing exercises and takes Sudafed for her sinuses. “I take daily pills, I take steroids,” she says. “I have two types of inhalers.”

Nowadays, as she navigates through Ontario’s wide, flat streets in her silver Honda CR-V, she likes to count each warehouse she passes. “There’s Target, Staples, UPS,” she says. “There’s one Amazon, and there’s another.”

"We Can’t Beat the System"

In response to concerns about emissions and air pollution, Amazon has said that it is planning to transition to electric transport and hydrogen-powered delivery trucks and vehicles and that the company “is on a path to powering our operations with 100 percent renewable energy by 2025.”

“We work hard to be a good neighbor and appreciate the partnership we have with many communities across the country, including Ontario,” said Barbara Agrait, an Amazon spokesperson.

Members of Ontario’s city council, including its mayor and mayor pro tem, did not respond to multiple queries from the Guardian.

In public meetings and statements, local leaders have said that the logistics industry has brought in much-needed tax revenue. They’ve said that when developers build new warehouses, often, they also make much-needed improvements to local infrastructure, such as repaving and widening roads to make way for trucks, and revamping aging plumbing and electrical systems.

City council members and local union representatives have also argued that the warehouses have created jobs, tens of thousands of them. Across the region, the warehousing and transportation industry employs some 214,000 people. Employment in the sector is up 39 percent since February 2020, following a boom in online shopping during the pandemic, according to an analysis by the Center for Economic Forecasting and Development at the University of California, Riverside, School of Business. The building boom has created jobs in construction, and related industries, while Amazon has become the largest employer in the Inland Empire.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian

Meanwhile, jobs outside of the warehousing industry are scarce and hard to find, several residents say.

Still, the work inside the warehouses can be grueling. Reporting by the Guardian found that warehouse workers were often injured at work. And local activists and residents have said that the warehouse and trucking jobs don’t pay enough for people to afford to live in Ontario, where the median price of a home is more than $500,000.

“I was able to make a living wage as a laborer, and have enough to buy a house and send my daughter to college,” says Juan Galván. “My kids don’t have those opportunities.” He says he still wonders why his daughter moved back to Ontario after studying and living in cities all over the world.

Activists have also said that council members have accepted thousands of dollars in donations from warehouse developers and other interests. A tally by Ian Ragen, a student at Pitzer College, found that city council members received at least $160,000 in campaign contributions from warehouse developers and related interests in 2020. Alan Wapner, the mayor pro tem, received $52,000 in donations from warehousing interests, such as commercial real estate firms and developers, and additional donations from a local farming family that owned much of the land under the upcoming South Ontario Logistics Center.

Members of the city council did not respond to specific queries about donations.

Residents are left with the impression that “they’re selling our community to these developers,” May says. “It seems like no matter how hard we work, we can’t beat the system.”

"The Warehouses Are Everywhere"

For some Ontario residents, it has been too much. “I always envisioned my entire life in this area,” says Danielle Cobarrubias, 23, who grew up in Ontario and neighboring Chino, and now lives in a new development that sits between an Amazon sorting center to the south, where her boyfriend used to work, and the upcoming Amazon hub to the north.

She recently started up a small-batch ice cream business in town. “I don’t want to leave all this behind,” she says. “But then, I think about all the trucks coming through our neighborhood.”

She says she doesn’t want to see her 3-year-old son, who already suffers from frequent nosebleeds, congestion, and trouble breathing at night, develop more serious respiratory issues.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian Photo: Pablo Unzueta/The Guardian

Jaime, the farmer across from the new Amazon warehouse, is planning to leave as well. His landlord has been fielding offers from warehouse developers—and has warned him that he has two or three years left before his lease will likely end.

“It’s a shame because the land here is really fertile,” he says. But these days the fumes and dust from the passing trucks make him wheeze after a long day out in the field. And he couldn’t afford to compete with developers to buy his own plot of land in town. “What can you do?” he says. “The warehouses are everywhere now.”

Editor’s Note: This article was produced by the Guardian US and co-published by Consumer Reports as part of a larger investigation into Amazon’s warehouses.

Correction: An earlier version of this article, originally published Sept. 13, 2022, stated that about 70 percent of children under 10 in San Bernardino County had been diagnosed with asthma. The correct figure is about 10 percent.